A PPC Lab Story

Performance ideas based on actual cases

Dr. Chad Peters

A Team That Should Have Been Electric

The Knibbs High School Bulldogs do not look like a traditional basketball team.

There is no true point guard but rather a duo. No classic back-to-the-basket center. No rigid two-guard, two-forward structure. This is a modern roster built for a modern game. Everyone handles it. Everyone moves. Everyone reads.

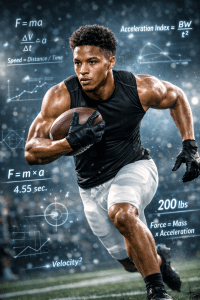

Petros is a 6’7 forward who plays above the rim and dunks like a highlight reel.

Jay is a 5’10 guard who is shifty as a meerkat and rains threes at nearly 45 percent when left open.

Nelly is a 6’4 powerhouse who looks more like a football player but moves like a dancer.

On paper, this team should be a problem.

In summer ball, they are.

The floor is open. The pace is light. Transition comes naturally. There are no real consequences and no real rewards. The game flows, the ball moves, and eighty points comes without force.

Then varsity season begins.

Same players. Same skills. Same spacing.

Different feel.

When the Game Changes Just Enough

To be fair, summer ball and high school varsity basketball are not the same environment.

Summer basketball is built to be fast, loose, and forgiving. Varsity basketball is tighter. Possessions matter more. Scouting exists. Momentum carries weight.

But the game itself has not fundamentally changed.

The rules are the same. The court is the same. The athletes are the same.

And yet, once the season starts, Knibbs finds itself grinding through games, stuck in the 45 to 50 point range, feeling like it takes a full quarter just to look comfortable.

What Everyone Thinks the Problem Is

If you sit in the stands long enough, you hear the same explanations every night.

They just need to wake up.

They look tight.

They are nervous.

They are thinking too much.

Players feel it. Fans see it. Coaches recognize it.

And at every game, I find myself having the same internal response. Not the same as the fans, but rather, “Nah. That is not it.”

The shots are not bad shots. They are just flat and too many miss, because of that.

The reads are not wrong. They are just late. So the. should-be incredible pass, is a almost and a turnover.

It feels less like a lack of effort and more like a band that knows the song but has not locked into rhythm yet.

So if it is not effort and it is not skill, what is actually different?

The Question That Actually Matters

The uncomfortable truth is this.

The team was not underprepared.

They were mis-prepared.

Most teams warm up the body and hope the rest shows up on its own. Jog. Stretch. Move through familiar patterns. Get loose. Break a sweat.

The intent is good.

The effect is limited.

Because the body does not turn on all at once.

Performance Order Matters

This is the part that gets missed.

Performance always expresses neurological before it expresses musculoskeletal.

Muscles do not decide when to fire. The nervous system does. Timing, coordination, and intent are set upstream long before strength or conditioning ever show up. These traits are compounded throughout the season and offseason in a similar way to how muscles size doesn’t just happen after a workout or two and conditioning doesn’t just improve after a few miles on the track.

When timing is sharp, movement looks confident.

When timing is late, everything feels forced.

This is not about effort. It is about order.

The Moment That Forces a Decision

By the end of pre-season, non-district play and tournaments, Knibbs sat with a record of 8 and 6.

Not bad.

Not great.

Competitive, but inconsistent.

District play was next.

Anyone who has coached long enough knows this is where margins shrink. Games get tighter. Early runs matter more. Deficits are harder to erase.

This is the moment where a decision has to be made.

If effort is not the issue.

If skill is not the issue.

If conditioning is not the issue.

Then what exactly are we trying to fix?

The Crossroads

Choose Your Own Adventure

This is where most teams stand without realizing it.

Path One

Fight Through It

Turn up the volume. Yell, Cheer, Motivate.

Cut rest., Add intensity early.

Push harder until energy appears.

It looks like preparation.

It feels like work.

For many teams, it works just enough. The season is solid. A few kids make all-district. You compete in your league.

But the ceiling does not really change. It’s basically “TRY HARDER,” than an actual system.

Path Two

Change the Lens

This path starts with a difficult admission.

This isn’t working as it should, we need CHANGE.

If the nervous system is the key, lets amplify the system. But there is a glaring problem.

It violates their internal definition of WORK

The bounces dont feel like a warmup.

There is so much rest time and quiet moments.

The feeling that we are watching time and we could be doing something else.

The system was not rejected because it was new.

It was rejected because it did not look like work.

Warm Up Versus Prime

This is where perspective matters.

What most people call a warm up is really just movement.

What high-level preparation requires is priming.

Priming sharpens timing.

It improves coordination.

It allows speed, skill, and confidence to show up early instead of waiting for adrenaline to force the issue later.

This is not something that had to be invented from scratch.

Track coaches figured this out years ago.

One of the most visible examples today is Tony Holler’s Feed the Cat system, which has finally gained the respect it deserves after decades of consistent results. It is often mislabeled as a warm up, when in reality it is a nervous system primer.

The misunderstanding is not the system.

It is the lens.

This Is Bigger Than One Tool

To be clear, this is not the only way elite performers prepare.

They also use visualization.

Intentional music.

Attention control.

Reduced scrolling.

Space for subconscious processing.

Different athletes respond to different inputs.

The common thread is always the same.

Preparation happens before fatigue.

Timing happens before intensity.

The nervous system sets the ceiling. The Potential.

And the speed in how fast it happens.

When the Switch Flips Earlier

Once Knibbs accepted that preparation might look different, the change was obvious.

They did not play harder.

They played sooner.

Petros did not need two possessions to find his legs.

Jay did not need three misses to feel comfortable.

Nelly did not force contact just to wake himself up.

Early success built confidence.

Confidence sped decision making.

Better decisions improved execution.

Energy and athleticism compounded instead of being chased.

The PPC Lab Takeaway

Most teams do not lose games in the fourth quarter.

They lose them in the first few minutes, before the game ever started, before they ever feel like themselves.

And sometimes the only thing standing in the way of change is not effort, talent, or toughness.

It is a modern system and their definition of work.

Knibbs decided to try something new.

They adopted a quick routine that was done where nobody could see them. Not on the court, but behind the scenes. For the rest of the year, at every practice and every game, they committed to a version of the Feed the Cats Atomic Speed Prep. A few of the exercises were modified to better match basketball demands, but the structure stayed the same. In nine minutes and five seconds, the team focused on bursts of five to eight seconds of maximal amplification, followed by roughly fifty seconds of rest.

It did not feel like work.

It did not look like a dynamic warm-up.

And it took constant encouragement and coaching to prevent those five seconds from being rushed, softened, or half-done.

But the team bought into trying something new.

The results were impossible to deny.

From the opening tip, the Bulldogs looked ON. Fewer dropped passes. Faster first steps. Sharper reactions. Fans started using words like faster, smarter, and better decisions without being prompted.

The team looked the same. Only BOUNCIER.

That year, the Bulldogs went on to significant district success, knocking off the perennial powerhouse that had dominated for the last decade. In one statement game, they opened with a 14–2 run against their crosstown rivals in the first five minutes of the first quarter.

The neurological preparation was not the only catalyst for change. But it acted like a volume knob, turning everything else up. Skill. Confidence. Timing. Belief.

Knibbs made a deep playoff run that season and set a new standard of success for their program.

Not by working harder.

But by preparing better.